- Betelgeuse might not be one star, but two! The smaller star could be 1.7 times the mass of our sun.

- Betelgeuse underwent a “great dimming” in recent years, causing some astronomers to think it might be on the verge of exploding as a supernova. But now a team of astronomers thinks the smaller star plays a role in Betelgeuse’s variability.

- If Betelgeuse has a companion, it might mean this star – the nearest red supergiant to Earth at 427 light-years – won’t go supernova for a long time.

Betelgeuse might have a buddy

A close analysis of the light curve – the record of starlight waxing and waning – for the old red supergiant star Betelgeuse has revealed the possibility of a 2nd star in the system. In other words, the single point of light we see as Betelgeuse might be 2 stars, with the smaller one about 1.7 times the mass of our sun. If this is so … is the explosion of Betelgeuse as a supernova still about to happen?

Betelgeuse is a variable star. It periodically changes in brightness and sometimes has irregular light changes. In recent years, it has undergone periods of dimming, which have caused astronomers to speculate that Betelgeuese – which is the nearest red supergiant to Earth at 427 light-years away – might be on the verge of going supernova.

Prior to the Great Dimming of Betelgeuse in 2019, astronomers said that, yes, Betelgeuse was due to explode, but perhaps not for thousands of years.

The out-of-sync variation of Betelgeuse

A trio of astronomers investigated a 2,170-day cycle of dimming and brightening of Betelgeuse. These scientists describe a long secondary period of variation, which isn’t unusual for stars of Betelgeuse’s class. However, the most common explanation for long secondary periods tends to be that the stars are in binary systems. And, they say, this explanation is specifically likely at Betelgeuse.

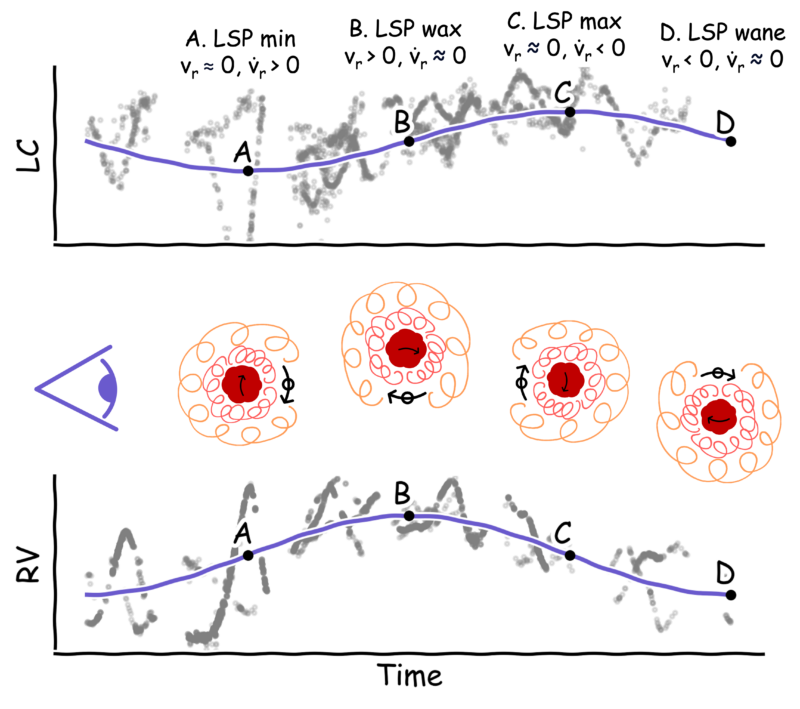

Variable stars like Betelgeuse pulse. They literally grow larger and smaller over time. We can study the variability of Betelgeuse in part via a a technique called radial velocity, the movement of something in space (in this case, the movement of the outer surface of Betelgeuse) toward or away from us. But, at Betelgeuse, the radial velocity variation doesn’t line up with the star’s light curve, the measurement of its waxing and waning in brightness. It’s like someone clapping on exactly the wrong beat.

Authors of the paper – astronomers Jared A. Goldberg, Meridith Joyce and László Molnár – claim this out-of-syncness is a smoking gun. Betelgeuse, they said, isn’t alone:

The light curve-radial velocity phase difference requires a companion to be behind Betelgeuse at the long secondary period luminosity minimum …

In other words, they said, Betelgeuse is brightest when the red supergiant star and its hypothetical little buddy are shining together, as seen from our earthly perspective.

This new work resulted in a study that was submitted August 17, 2024, to the online scholarly archive arXiv.

The Great Dimming and its aftermath

Back in 2019, Betelgeuse’s brightness dropped dramatically and unexpectedly. The turning down of the lights lasted until 2020. Later, that time of dimming for Betelgeuse became known as the Great Dimming. There was much speculation that Betelgeuse might be about to explode! But it didn’t explode, and, later, dust was offered as an explanation for the dimming.

Yet the Great Dimming trigged a wave of interest in Betelgeuse. It caught people’s imaginations: would we see this familiar red star blaze forth in brightness, becoming the brightest star in our night sky, perhaps even visible in the daytime?

That’s why the authors of the new paper describe their results about Betelgeuse as groundbreaking:

These studies have led to revisions in our understanding of Betelgeuse’s behavior and fundamental parameters, as well as opened new lines of inquiry into some of Betelgeuse’s less well-understood properties …

So is Betelgeuse a binary? The notion Betelgeuse is a binary star dates back at least 25 years. But observations and interpretations since the Great Dimming dust storm strongly reinforce the idea. And the authors say dust is important to understanding what’s going on:

While such early versions of the binarity hypothesis were most concerned with whether a close companion could induce low-frequency modes on the primary star, the current leading theory is that the timescale of the LSP period is set by the orbital time of a low-mass companion, and the mechanism of dimming and brightening involves the formation and removal of dust along the line of sight in phase with the companion’s orbit.

Supernova soon? Not if it’s a binary star

Knowing if another, smaller star lurks off the shoulder of Orion may tell us how long Betelgeuse has to live. Betelgeuse is still expected one day – maybe soon, maybe in thousands of years – to explode as a supernova.

When it blows depends on whether a companion star is making it move.

Betelgeuse has another well-known periodicity in its orbit. This one fluctuates on a cycle of about 420 days, and is believed to be the star’s fundamental mode. If it isn’t, Betelgeuse will go supernova sooner than later.

The paper explains:

If the 2,100-day periodicity is the fundamental mode, it implies a large and observationally contentious radius for Betelgeuse. Further, it would place Betelgeuse’s current evolutionary stage beyond the onset of core carbon burning, suggesting that a supernova explosion is imminent within the next several dozen to several hundred years. If, on the other hand, the 2,100-day periodicity is an LSP, Betelgeuse is comfortably within in its core helium burning phase and not due for an explosion for hundreds of thousands of years.

This means things don’t look good for those hoping to see a nearby supernova in their lifetimes. The trio of authors say their data means Betelgeuse probably isn’t alone:

We overview all of the scenarios proposed as an explanation for Betelgeuse’s LSP, demonstrating critical flaws in all but one case: Betelgeuse has a companion that interacts with the star’s dusty circumstellar environment.

Not in our lifetime

When Betelgeuse finally blows, it’ll probably be visible in the daytime. But that might not be for at least hundreds of thousands of years, according to the ideas presented in this new research.

Bottom line: A recently published study suggests the red giant star Betelgeuse might have a sun-size companion. Betelgeuse’s buddy would explain some of the intricacies in astronomers’ measurements of the star’s brightness and variability.

Read more: Betelgeuse: The Great Dimming of 2019-2020

Source: A Buddy for Betelgeuse: Binarity as the Origin of the Long Secondary Period in b Orionis