Looking outward into our Milky Way galaxy, astronomers have discovered over 5,500 confirmed exoplanets, or planets orbiting distant stars. And there are thousands more exoplanet candidates. But possible exomoons orbiting these distant worlds would be much tougher to see. So astronomers have reported only a handful so far. But these discoveries are hard to come by. And some discoveries aren’t certain. For example, giant exomoons supposedly orbited two distant gas giant worlds, known as Kepler-1625b and Kepler-1708b. On December 8, 2023, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research and the Sonnenberg Observatory – both in Germany – said those two giant exomoons might not exist.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed doubts in Nature Astronomy on December 5.

The 2024 lunar calendars are here! Best Christmas gifts in the universe! Check ’em out here.

Giant exomoons around Kepler-1625b and Kepler-1708b?

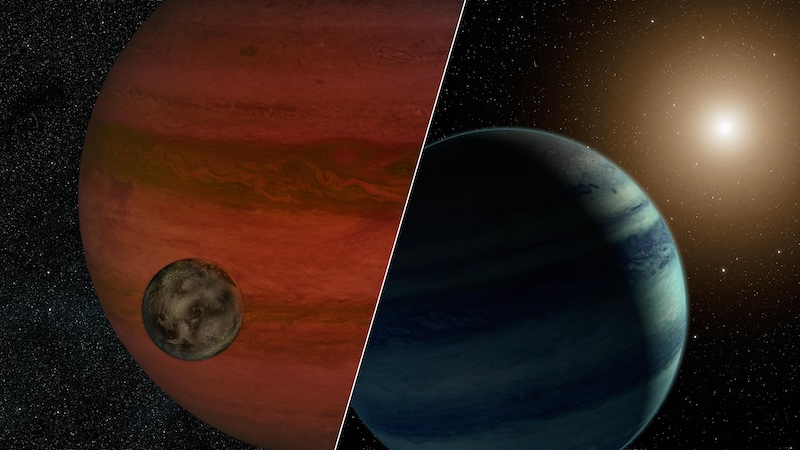

Kepler-1625b and Kepler-1708b are gas giant planets similar to our solar system’s biggest planet, Jupiter. We know all of the gas and ice giant planets in our solar system – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune – have numerous moons. Saturn holds the record with 146 known moons! So it seems likely that giant worlds in other planetary systems have moons as well.

It was in 2018 that scientists at Columbia University in New York said they’d found evidence of a huge moon orbiting Kepler-1625b. The researchers found it in data from the Kepler Space Telescope. But then things got confusing. When researchers cleaned the data of extraneous noise, evidence for the moon disappeared. But then, still later, when the Hubble Space Telescope subsequently observed Kepler-1625b, the moon was back!

It was in 2022 that astronomers found the second possible giant moon. This one seemed to orbit Kepler-1708b. This moon, if real, was huge, even larger than Earth.

Scientists have debated their existence since their discoveries. The paper stated [emphasis added by EarthSky]:

The best exomoon candidates so far are two nearly Neptune-sized bodies orbiting the Jupiter-sized transiting exoplanets Kepler-1625b and Kepler-1708b. But their existence has been contested.

So the best exomoon candidates found so far are now in doubt.

Giant doubts about the giant exomoons

The tentative discovery of the two giant exomoons was exciting, of course. They were unusual in that both of them were much larger than even the largest moons in our own solar system. But, if they truly existed and truly were so large, that fact would help explain why astronomers were able to detect them in the data.

Which brings us to now. The new study from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research and the Sonnenberg Observatory casts serious doubts on the original discoveries. The researchers found scenarios without moons that can explain the observations just as well as ones with moons. As René Heller, first author of the new paper at Max Planck Institute, stated:

We would have liked to confirm the discovery of exomoons around Kepler-1625b and Kepler-1708b. But unfortunately, our analyses show otherwise.

Michael Hippke at Sonnenberg is the second co-author of the new paper. As for Kepler-1708b, he said:

The probability of a moon orbiting Kepler-1708b is clearly lower than previously reported. The data do not suggest the existence of an exomoon around Kepler-1708b.

Stellar limb darkening

So what about Kepler-1625b? Unfortunately, the results are similar. Kepler and Hubble had observed transits of the planet in front of its star. During the transit, the telescopes had seen an instantaneous variation in brightness across the disk of the star. This is called stellar limb darkening, where the outer limb (edge) of the disk looks darker than the center.

This darkening appeared different, however, in Kepler than it did Hubble. Why? The two telescopes are sensitive to different wavelengths of light. The researchers now propose that the modeling of that effect can explain the observations better than an exomoon.

False positives

The results are applicable not only to these two exomoon candidates, but perhaps others as well. The findings suggest that exomoon searches overall are prone to produce false-positive results. For example, a light curve similar to that of Kepler-1625b will have a false positive rate of about 11%. Heller said:

The earlier exomoon claim by our colleagues from New York was the result of a search for moons around dozens of exoplanets. According to our estimates, a false-positive finding is not at all surprising, but almost to be expected.

On the other hand, we should be able to detect some exomoons with current technology. But they would still need to be quite large – twice the size of our solar system’s largest moon Ganymede – and have wide orbits around their planets, the researchers said.

Other exomoon candidates

While the new results are disappointing, it doesn’t mean there are no giant exomoons. As we mentioned above, there are still some other current candidates. Astronomers found the first candidate in 2014. They called that possible exomoon system MOA-2011-BLG-262. The astronomers couldn’t further confirm it, however, since they found it during a gravitational microlensing event, which occurs only once.

In 2019, astronomers said they found another exomoon candidate, orbiting the hot Jupiter gas giant planet WASP-49b. The data suggested that this moon might be hypervolcanic, like Jupiter’s moon Io.

Then, in 2020, scientists at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada, said they may have found six more exomoons! They range from 200 to 3,000 light-years away.

Future observations

To sum up, it’s still difficult to confirm any exomoon candidates. Confirmation might have to wait for observations from even better telescopes, such as the upcoming PLATO mission. The paper said:

Thus, any possible exomoon detection in the archival Kepler data or with upcoming PLATO observations will necessarily be odd when compared to the solar system moons. In this sense, the now refuted claims of Neptune- or super-Earth-sized exomoons around Kepler-1625 b and Kepler-1708 b could nevertheless foreshadow the first genuine exomoon discoveries that may lay ahead.

Bottom line: Astronomers in Germany say that two possible giant exomoons probably don’t actually exist. That’s disappointing, but there are still some other candidates.

Source: Large exomoons unlikely around Kepler-1625 b and Kepler-1708 b

Via Max-Planck-Gesellschaft

Read more: Astronomers may have spotted the first exomoon!

Read more: A new way to search for exomoons