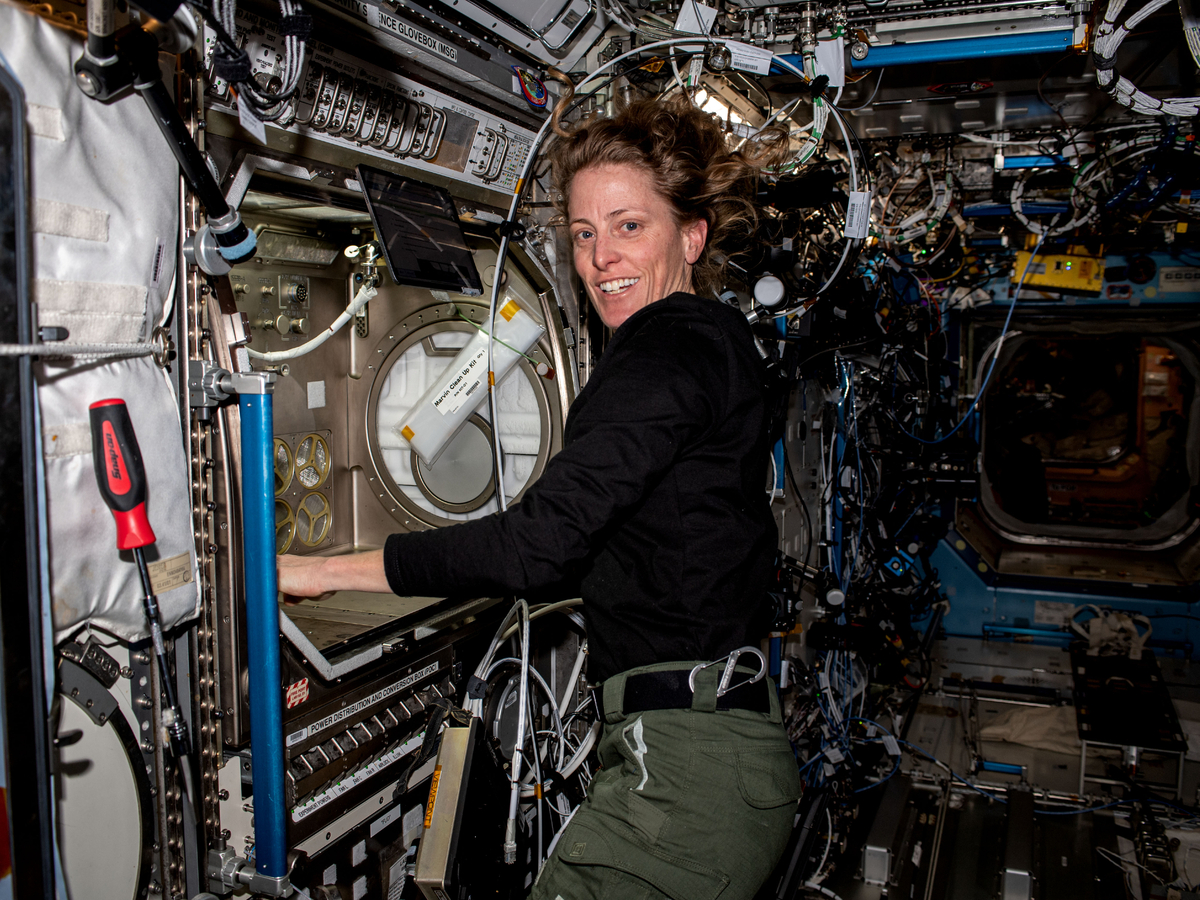

NASA astronaut and Expedition 70 Flight Engineer Loral O’Hara is pictured working with the Microgravity Science Glovebox, a contained environment crew members use to handle hazardous materials for various research investigations in space.

NASA

hide caption

toggle caption

NASA

NASA astronaut and Expedition 70 Flight Engineer Loral O’Hara is pictured working with the Microgravity Science Glovebox, a contained environment crew members use to handle hazardous materials for various research investigations in space.

NASA

Few humans have had the opportunity to see Earth from space. And for astronauts living in the International Space Station like Loral O’Hara, that view never gets old.

But there’s nothing like the first time.

“You know, you see it in photographs, but that doesn’t compare at all to seeing it in person for the first time in 3D,” O’Hara told NPR Short Wave host Regina G. Barber in a recent interview. “I just saw the ocean and the clouds — this blue and white marble against the blackness of space — and it was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen.”

O’Hara is a flight engineer for NASA’s Expedition 70 crew, who launched into space in September 2023. She and her team spent the last six months researching a range of topics: How the human brain and body adapt to microgravity, 3D-printed human heart tissue and how space changes the immune systems of plants.

Loral O’Hara talkes to Regina G. Barber

NASA

YouTube

One of these investigations is the Complement of Integrated Protocols for Human Exploration Research program, or CIPHER. It aims to help researchers understand how living in space changes human health and psychology.

On Earth, gravity keeps blood and other fluids relatively low in the body. But when astronauts live in microgravity these fluids are pushed up towards the heart and heart, which can cause swelling, congestion and even vision and hearing changes.

O’Hara says these changes can be disorienting for astronauts — and sometimes make them feel sick.

“I’ve been congested for about a month now and it’s not going away, she says. “It’s kind of my new normal.”

Onboard the ISS, O’Hara says astronauts keep tabs on these potential health risks, performing regular eye exams and ultrasounds to collect data.

The hope is to use this data not only for microgravity research, but also for research on Earth. For example, researchers know astronauts lose about 1% to 2% of their bone density per month during spaceflight. So, O’Hara and her team are analyzing bone marrow stem cells in order to better understand both this bone loss and normal aging on Earth.

O’Hara says the changes aren’t just physical either. She’s even had new types of dreams since she boarded the ISS last September. She says she often finds herself in small, tight spaces, looking for things on the space station.

“They’re not space nightmares, but they’re not, you know, pleasant dreams, floating, looking at Earth,” she says.

Maybe one day an experiment will explain that, too.

Want to hear more about space? Email us at shortwave@npr.org.

Listen to Short Wave on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts.

Listen to every episode of Short Wave sponsor-free and support our work at NPR by signing up for Short Wave+ at plus.npr.org/shortwave.

Today’s episode was produced by Rachel Carlson. It was edited by Rebecca Ramirez. Rebecca and Rachel also checked the facts. Patrick Murray was the audio engineer.