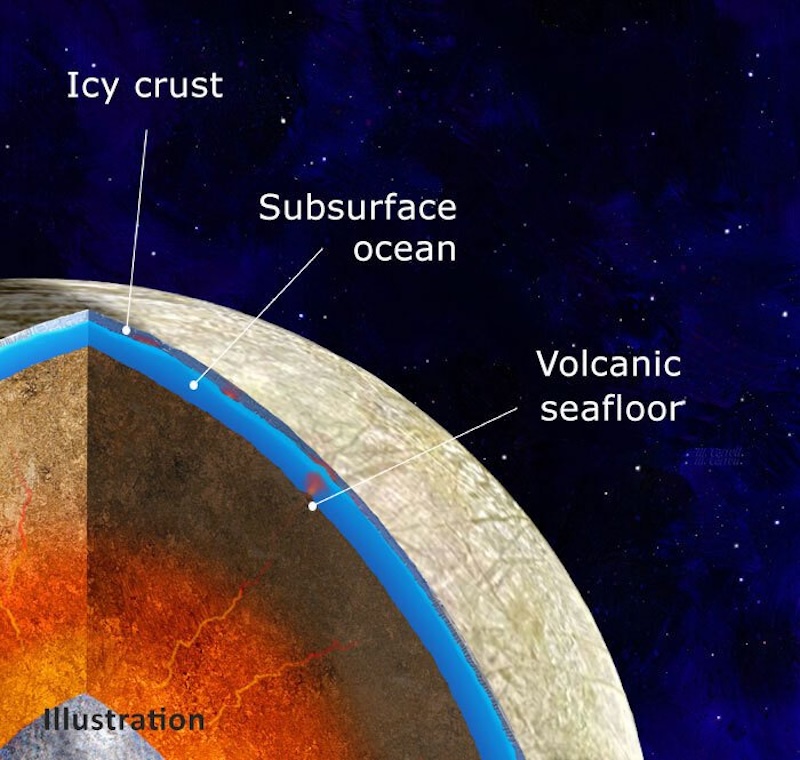

- Jupiter’s large moon Europa seems to have an ocean, buried beneath a crust of ice. Astronomers have long thought Europa’s ocean might be habitable by microbes or other organisms. That’s one reason a spacecraft, Europa Clipper, is scheduled to launch to Europa in October, 2024.

- Now a new study suggests Europa’s seafloor might not be geologically active enough for volcanos and hydrothermal vents. That would limit chemical reactions needed to sustain life in Europa’s ocean.

- The new study uses computer modeling to simulate whether rocks on the floor of Europa’s subsurface ocean are strong or weak. The results suggest the rocks are too rigid for magma to escape to the ocean from below. Meanwhile, many other previous studies have supported an active seafloor, and habitable ocean, for Europa.

Jupiter’s moon Europa has fascinated scientists and the public alike ever since Voyager 1 and 2 found the first hints of a global subsurface ocean in 1979. Subsequent studies by other spacecraft confirmed the discovery. They also found that the ocean is salty like oceans on Earth, and potentially habitable, at least for microorganisms. But now, a team of U.S. scientists is throwing some cold water on the prospects for life in Europa’s ocean. They said on March 12, 2024, that there might not be enough volcanic activity on the seafloor to sustain active biology. Is Europa geologically – and otherwise – dead inside?

Read more: What does “habitable” mean to scientists?

Austin Green, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, and Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis, presented the new findings at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC 2024) in The Woodlands, Texas, earlier this month.

They discussed their two new peer-reviewed LPSC papers, which you can read here and here.

Hello friends! It’s time for our annual crowd-funder. Please donate now to help EarthSky keep going!

2 new modeling studies of Europa

The new results come from two new modeling studies of Europa’s interior. Essentially, the studies suggest that Europa’s seafloor may be inactive, with little to no geological activity. On Earth, seafloor volcanoes and hydrothermal vents provide heat and nutrients for a wide variety of life deep in the oceans.

But on Europa, the seafloor may be inert and too solid for magma to move through from below. Thus, hydrothermal vents wouldn’t be able to form. In addition, the outer ice crust may also resist seismic fracturing. That would mean there is little to no heat and freshly produced rock to drive geochemical reactions in the ocean. If so, then the ocean could be stagnant and lifeless.

Green said:

If this volcanism is necessary for habitability, Europa’s ocean is uninhabitable.

Assessing Europa’s seafloor

Scientists think that Europa’s seafloor is about 80 miles (130 km) below the surface. As Byrne pointed out, Europa is mostly rock, with an ocean layer inside it:

When we’re thinking of icy worlds generally, we should be thinking of them as rocky worlds as well. Because the vast majority of Europa’s volume and mass is rock.

The researchers wanted to assess the strength of Europa’s lithosphere. That is the rigid silicate rock that resides at the top of the moon’s rocky mantle, ie. the seafloor.

Read more: A message to Europa from the people of Earth

Are Europa’s seafloor rocks strong or weak?

They proposed two scenarios, a strong one and a weak one. In the strong scenario, the seafloor rocks would be rigid and the ocean water wouldn’t alter them. The ocean itself would also be deeper. This would make the rocks even more solid, due to the increased water pressure.

But if the weaker scenario was correct, then the water would make the rocks weaker. The ocean would also be shallower.

Jupiter’s immense gravity tugs and pulls on Europa. This causes stress in the rocks. The researchers calculated the strength of the rocks, accounting for that stress and how much the moon had cooled ever since it first formed billions of years ago. The results were disappointing although not definitively conclusive. They suggested that the seafloor rocks remained quite strong and resisted slipping or cracking, even in the weak scenario. Fresh exposures of rock are necessary for the chemical reactions that can sustain life. Byrne said:

I don’t think there’s anything happening on the ocean floor.

Are there conditions today at the surface of the Europa sea floor that could sustain some kind of biology? Our findings say it seems difficult, which is science for, ‘probably not.’

Simulating Europa’s mantle

The other research team, led by Green, looked at Europa’s mantle instead. They simulated melted (molten) rock in the moon’s mantle to see if magma could rise up in dikes, all the way to the lithosphere and onto the seafloor. All the simulations showed that it would be difficult. As it turned out, the magma rose only a few miles before it crystallized again. As Green noted:

How did they do? They did really, really, really bad.

Still hope for life on Europa

There is still some reason for optimism, however, according to two other researchers. William McKinnon, a planetary scientist at Washington University, pointed out that magma can still find a way to erupt onto the surface of moons and planets that were considered to be geologically dead:

Bodies like the moon and Mars have managed to erupt magma.

He also mentioned that the models in the new studies are fairly simple. And with a lack of other solid data, there is room for error. He also added, however:

Maybe today the situation is not right for volcanism. It could easily come and go. And if a primitive biosphere did somehow arise during a period of volcanism, could any of that life, or even signs of it, persist to today?

In addition, Francis Nimmo, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, noted that our own moon is still seismically active, even though models suggested it shouldn’t be. He said:

The moon is one place where we know we have tidally driven quakes.

Other studies

It should also be noted that other previous studies have suggested that Europa’s seafloor may indeed be active. One study from 2021 said that the seafloor should be hot enough for active seafloor volcanoes. Those volcanoes would provide energy for hydrothermal vents, much like on Earth’s seafloors.

So right now, the jury is still out on whether Europa’s seafloor is active or not. The answer will have direct implications for the possibility of life – even if just microscopic – in Europa’s vast ocean. That answer may have to wait for when NASA’s Europa Clipper mission arrives at Europa. Clipper is scheduled to launch on October 10, 2024 and arrive in 2030.

Another recent study also found evidence that carbon dioxide deposits on Europa’s surface originated from its ocean. This could indicate a habitable environment in the ocean.

And on March 20, 2024, scientists said that Europa’s outer ice shell is now estimated to be at least 12 miles (20 km) thick. This could affect how much material is exchanged between the surface and subsurface ocean, with implications for habitability.

Bottom line: Two new studies suggest the subsurface ocean on Jupiter’s moon Europa may not be as habitable as previously thought, due to a geologically inactive seafloor.

Via Science

Source: Likely Little to No Geological Activity on the Europan Seafloor

Source: No Magmatic Driving Force for Europan Seafloor Volcanism

Read more: Active seafloor volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Europa?

Read more: Did Europa’s carbon dioxide come from its ocean?