An unusual group of stars in the Orion constellation have revealed their secrets. FU Orionis, a double star system, first caught astronomers’ attention in 1936 when the central star suddenly became 1,000 times brighter than usual. This behavior, expected from dying stars, had never been seen in a young star like FU Orionis.

The strange phenomenon inspired a new classification of stars sharing the same name (FUor stars). FUor stars flare suddenly, erupting in brightness, before dimming again many years later.

It is now understood that this brightening is due to the stars taking in energy from their surroundings via gravitational accretion, the main force that shapes stars and planets.

However, how and why this happens remained a mystery—until now, thanks to astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

“FU Ori has been devouring material for almost 100 years to keep its eruption going. We have finally found an answer to how these young outbursting stars replenish their mass,” explains Antonio Hales, deputy manager of the North American ALMA Regional Center, scientist with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, and lead author of this research, published today in The Astrophysical Journal.

“For the first time we have direct observational evidence of the material fueling the eruptions,” says Hales.

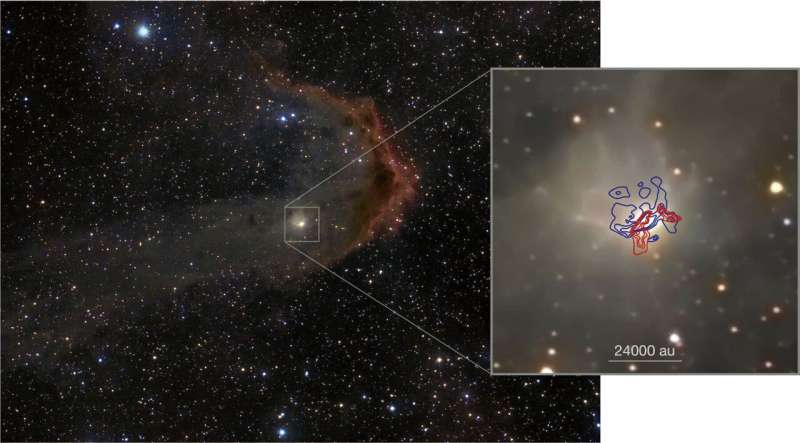

ALMA observations revealed a long, thin stream of carbon monoxide falling onto FU Orionis. This gas didn’t appear to have enough fuel to sustain the current outburst. Instead, this accretion streamer is believed to be a leftover from a previous, much larger feature that fell into this young stellar system.

“It is possible that the interaction with a bigger stream of gas in the past caused the system to become unstable and trigger the brightness increase,” explains Hales.

Astronomers used several configurations of ALMA antennas to capture the different types of emission coming from FU Orionis, and detect the flow of mass into the star system. They also combined novel numerical methods to model the mass flow as an accretion streamer and estimate its properties.

“We compared the shape and speed of the observed structure to that expected from a trail of infalling gas, and the numbers made sense,”, says Aashish Gupta, a Ph.D. candidate at European Southern Observatory (ESO), and a co-author of this work, who developed the methods used to model the accretion streamer.

“The range of angular scales we are able to explore with a single instrument is truly remarkable. ALMA gives us a comprehensive view of the dynamics of star and planet formation, spanning from large molecular clouds in which hundreds of stars are born, down to the more familiar scales of solar systems,” adds Sebastián Pérez of Universidad de Santiago de Chile (USACH), director of the Millennium Nucleus on Young Exoplanets and their Moons (YEMS) in Chile, and co-author of this research.

These observations also revealed an outflow of slow-moving carbon monoxide from FU Orionis. This gas is not associated with the most recent outburst. Instead, it is similar to outflows observed around other protostellar objects.

Adds Hales, “By understanding how these peculiar FUor stars are made, we’re confirming what we know about how different stars and planets form. We believe that all stars undergo outburst events. These outbursts are important because they affect the chemical composition of the accretion disks around nascent stars and the planets they eventually form.”

“We have been studying FU Orionis since ALMA’s first observations in 2012,” adds Hales. It’s fascinating to finally have answers.”

More information:

A. S. Hales et al, Discovery of an Accretion Streamer and a Slow Wide-angle Outflow around FU Orionis, The Astrophysical Journal (2024). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad31a1

Provided by

National Radio Astronomy Observatory

Citation:

Orion’s erupting star system reveals its secrets (2024, April 29)

retrieved 29 April 2024

from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.