Some scientists dream of exploring planets with “smart” spacecraft that know exactly what data to look for, where to find it, and how to analyze it. Although making that dream a reality will take time, advances made with NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover offer promising steps in that direction.

For almost three years, the rover mission has been testing a form of artificial intelligence that seeks out minerals in the Red Planet’s rocks. This marks the first time AI has been used on Mars to make autonomous decisions based on real-time analysis of rock composition.

The software supports PIXL (Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry), a spectrometer developed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. By mapping the chemical composition of minerals across a rock’s surface, PIXL allows scientists to determine whether the rock formed in conditions that could have been supportive of microbial life in Mars’ ancient past.

Called “adaptive sampling,” the software autonomously positions the instrument close to a rock target, then looks at PIXL’s scans of the target to find minerals worth examining more deeply. It’s all done in real time, without the rover talking to mission controllers back on Earth.

“We use PIXL’s AI to home in on key science,” said the instrument’s principal investigator, Abigail Allwood of JPL. “Without it, you’d see a hint of something interesting in the data and then need to rescan the rock to study it more. This lets PIXL reach a conclusion without humans examining the data.”

Data from Perseverance’s instruments, including PIXL, helps scientists determine when to drill a core of rock and seal it in a titanium metal tube so that it, along with other high-priority samples, could be brought to Earth for further study as part of NASA’s Mars Sample Return campaign.

Adaptive sampling is not the only application of AI on Mars. About 2,300 miles (3,700 kilometers) from Perseverance is NASA’s Curiosity, which pioneered a form of AI that allows the rover to autonomously zap rocks with a laser based on their shape and color.

Studying the gas that burns off after each laser zap reveals a rock’s chemical composition. Perseverance features this same ability, as well as a more advanced form of AI that enables it to navigate without specific direction from Earth. Both rovers still rely on dozens of engineers and scientists to plan each day’s set of hundreds of individual commands, but these digital smarts help both missions get more done in less time.

“The idea behind PIXL’s adaptive sampling is to help scientists find the needle within a haystack of data, freeing up time and energy for them to focus on other things,” said Peter Lawson, who led the implementation of adaptive sampling before retiring from JPL. “Ultimately, it helps us gather the best science more quickly.”

Using AI to Position PIXL

AI assists PIXL in two ways. First, it positions the instrument just right once the instrument is in the vicinity of a rock target. Located at the end of Perseverance’s robotic arm, the spectrometer sits on six tiny robotic legs, called a hexapod. PIXL’s camera repeatedly checks the distance between the instrument and a rock target to aid with positioning.

Temperature swings on Mars are large enough that Perseverance’s arm will expand or contract a microscopic amount, which can throw off PIXL’s aim. The hexapod automatically adjusts the instrument to get it exceptionally close without coming into contact with the rock.

“We have to make adjustments on the scale of micrometers to get the accuracy we need,” Allwood said. “It gets close enough to the rock to raise the hairs on the back of an engineer’s neck.”

Making a mineral map

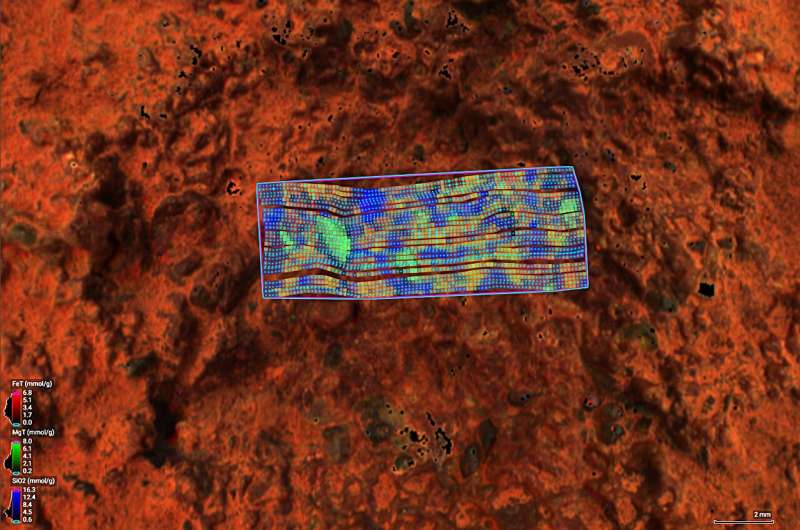

Once PIXL is in position, another AI system gets the chance to shine. PIXL scans a postage-stamp-size area of a rock, firing an X-ray beam thousands of times to create a grid of microscopic dots. Each dot reveals information about the chemical composition of the minerals present.

Minerals are crucial to answering key questions about Mars. Depending on the rock, scientists might be on the hunt for carbonates, which hide clues to how water may have formed the rock, or they may be looking for phosphates, which could have provided nutrients for microbes, if any were present in the Martian past.

There’s no way for scientists to know ahead of time which of the hundreds of X-ray zaps will turn up a particular mineral, but when the instrument finds certain minerals, it can automatically stop to gather more data—an action called a “long dwell.” As the system improves through machine learning, the list of minerals on which PIXL can focus with a long dwell is growing.

“PIXL is kind of a Swiss army knife in that it can be configured depending on what the scientists are looking for at a given time,” said JPL’s David Thompson, who helped develop the software. “Mars is a great place to test out AI since we have regular communications each day, giving us a chance to make tweaks along the way.”

When future missions travel deeper into the solar system, they’ll be out of contact longer than missions currently are on Mars. That’s why there is strong interest in developing more autonomy for missions as they rove and conduct science for the benefit of humanity.

Citation:

Here’s how AI Is changing NASA’s Mars rover science (2024, July 16)

retrieved 16 July 2024

from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.