Reprinted from NASA.

Voyager 2 passes by Neptune, 35 years ago

Thirty-five years ago, on August 25, 1989, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft made a close flyby of Neptune. It gave humanity its 1st close-up of our solar system’s 8th planet. It also marked the end of the Voyager mission’s Grand Tour of the solar system’s 4 giant planets, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. No other spacecraft has visited Neptune since.

Ed Stone, a professor of physics at Caltech and Voyager’s project scientist since 1975, said:

The Voyager planetary program really was an opportunity to show the public what science is all about. Every day we learned something new.

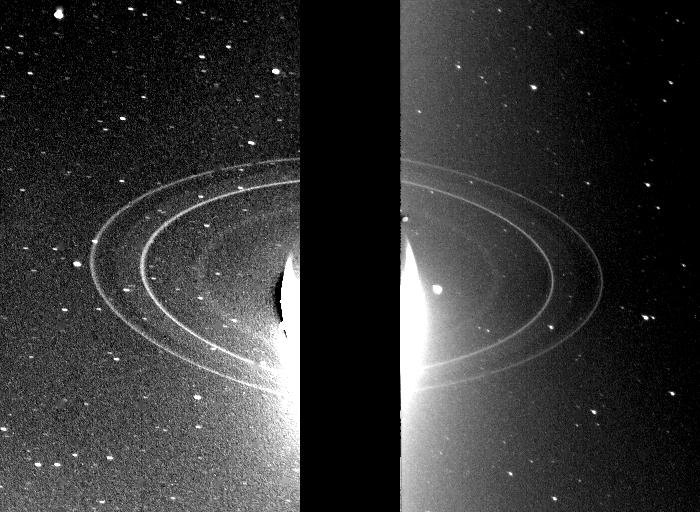

Wrapped in teal and cobalt-colored bands of clouds, the planet that Voyager 2 revealed looked like a blue-hued sibling to Jupiter and Saturn. The blue on Neptune indicates the presence of methane. A massive, slate-colored storm was dubbed the Great Dark Spot, similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. Plus, Voyager 2 discovered six new moons and four rings.

Voyager 2 also visited Triton

During the encounter, the engineering team carefully changed the probe’s direction and speed so that it could do a close flyby of the planet’s largest moon, Triton. The flyby showed evidence of geologically young surfaces and active geysers spewing material skyward. This indicated that Triton was not simply a solid ball of ice even though it had the lowest surface temperature of any natural body observed by Voyager: -391 degrees Fahrenheit (-235 degrees Celsius).

Voyager 2 onward to interstellar space

The conclusion of the Neptune flyby marked the beginning of the Voyager Interstellar Mission. Forty-seven years after launch, Voyager 2 and its twin, Voyager 1 (which had also flown by Jupiter and Saturn), continue to send back dispatches from the outer reaches of our solar system. At the time of the Neptune encounter, Voyager 2 was about 2.9 billion miles (4.7 billion km) from Earth. Today it is 12.7 billion miles (20 billion km) from us. The faster-moving Voyager 1 is 15.2 billion miles (24 billion km) from Earth.

Getting there

By the time Voyager 2 reached Neptune, the Voyager mission team had completed five planetary encounters. But the big blue planet still posed unique challenges.

Neptune is about 30 times farther from the sun than Earth. So, the icy giant receives only about 0.001 times the amount of sunlight that Earth does. In such low light, Voyager 2’s camera required longer exposures to get quality images. But the spacecraft would reach a maximum speed of about 60,000 mph (90,000 kph) relative to Earth. So, a long exposure time would make the image blurry. (Imagine trying to take a picture of a roadside sign from the window of a speeding car.)

So the team programmed Voyager 2’s thrusters to fire gently during the close approach, thus rotating the spacecraft to keep the camera focused on its target without interrupting the spacecraft’s overall speed and direction.

Receiving the radio signals from Neptune

The probe’s distance meant by the time radio signals from Voyager 2 reached Earth, they were weaker than other flybys. But the spacecraft had the advantage of time. The Voyagers communicate with Earth via the Deep Space Network, or DSN, which utilizes several radio antennas. They are in Madrid, Spain; Canberra, Australia; and Goldstone, California. During Voyager 2’s Uranus encounter in 1986, the three largest DSN antennas were 64 meters (210 feet) wide. To assist with the Neptune encounter, the DSN expanded the dishes to 70 meters (230 feet). They also included nearby non-DSN antennas to collect data, including another 64-meter (210 feet) dish in Parkes, Australia. And multiple 25-meter (82 feet) antennas at the Very Large Array in New Mexico.

The effort ensured that engineers could hear Voyager loud and clear. It also increased how much data could reach Earth in a given period, thus enabling the spacecraft to send back more pictures from the flyby.

Being there

In the week leading up to that August 1989 close encounter, the atmosphere was electric at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, which manages the Voyager mission. As images taken by Voyager 2 during its Neptune approach made the four-hour journey to Earth, Voyager team members would crowd around computer monitors around the Lab to see. Stone said:

One of the things that made the Voyager planetary encounters different from missions today is that there was no internet that would have allowed the whole team and the whole world to see the pictures at the same time. The images were available in real time at a limited number of locations.

But the team was committed to giving the public updates as quickly as possible. So from August 21 to August 29, they would share their discoveries with the world during daily press conferences. On August 24, a program called Voyager All Night broadcast regular updates from the probe’s closest encounter with the planet, which took place at 4 a.m. GMT (9 p.m. in California on August 24).

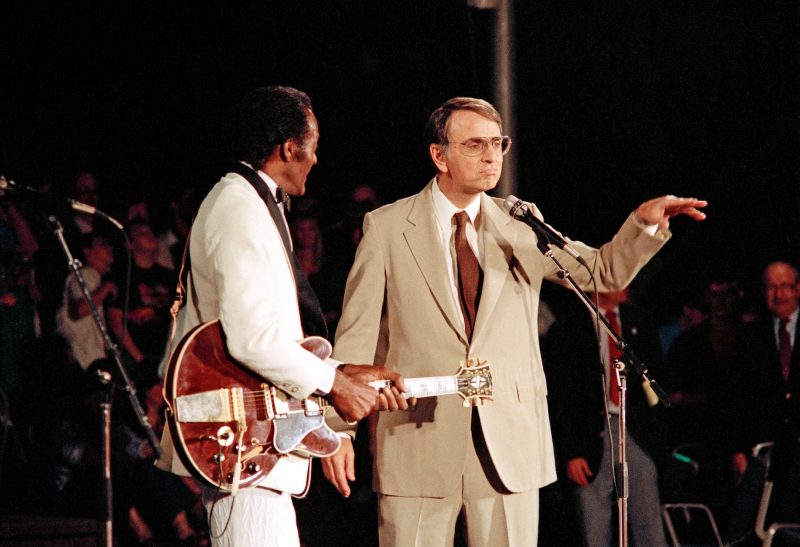

The next morning, Vice President Dan Quayle visited the lab to commend the Voyager team. That night, Chuck Berry, whose song Johnny B. Goode was included on the Golden Record that flew with both Voyagers, played at JPL’s celebration of the feat.

Voyagers were successful and continue today

Of course, the Voyagers’ achievements extend far beyond that historic week over three decades ago. Both probes have now entered interstellar space after exiting the heliosphere, the protective bubble around the planets created by a high-speed flow of particles and magnetic fields spewed outward by our sun.

They are reporting back to Earth on the “weather” and conditions from this region filled with the debris from stars that exploded elsewhere in our galaxy. They have taken humanity’s first tenuous step into the cosmic ocean where no other operating probes have flown.

Voyager data also complement other missions, including NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX), which is remotely sensing that boundary where particles from our sun collide with material from the rest of the galaxy. And NASA is preparing the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP), due to launch in 2025, to capitalize on Voyager observations.

The Voyagers send their findings back to DSN antennas with 13-watt transmitters, about enough power to run a refrigerator light bulb. Stone said:

Every day they travel somewhere that human probes have never been before. Years after launch, and they’re still exploring.

More information about the Voyager mission

More images of Neptune taken by Voyager 2

Bottom line: It has been 35 years since Voyager 2 visited Neptune as part of the Voyagers’ Grand Tour of our solar system’s four giant planets. As of today, no other earthly spacecraft has returned to Neptune.

Via NASA

Where is Voyager 2 going? And when will it get there?

Read more: Why are the Voyager spacecraft getting closer to Earth?