Unusually long gamma-ray bursts require more exotic origins than typical gamma-ray bursts. This animation illustrates one proposed explanation. It shows a black hole eating a stellar-mass star. As the black hole makes its last few orbits, it pulls large amounts of gas from the star. The system begins to shine brightly in X-rays. Then, as the black hole enters the main body of the star, it rapidly consumes stellar matter, resulting in a gamma-ray burst. Video via NASA/ LSU/ Brian Monroe.

EarthSky’s 2026 lunar calendar is available now. Get yours today! Makes a great gift.

- Astronomers spotted a gamma-ray burst – named GRB 250702B – on July 2, 2025. It’s the longest gamma-ray burst ever recorded, lasting at least seven hours, nearly double the previous record.

- The rare, long-duration burst may reveal new ways to create gamma-ray bursts. And it suggests there may be previously unseen types of cosmic explosions.

- One explanation is that a black hole about three times the sun’s mass – with an event horizon just 11 miles (18 kilometers) across – merged with a companion star.

NASA published this original story on December 8, 2025. Edits by EarthSky.

Gamma-ray burst is the longest on record

Astronomers have been poring over a flood of data from NASA satellites and other facilities. They’re trying to work out what was responsible for an extraordinary cosmic outburst discovered on July 2, 2025.

The event was a gamma-ray burst, the most powerful class of cosmic explosions. Most gamma-ray bursts last only a minute. But this initial wave of gamma rays lasted at least seven hours, and jet activity continued for days.

Researchers have been eagerly discussing their findings. They agree the unprecedented event likely heralds a new kind of stellar explosion. And they said the best explanation for the outburst is that a black hole consumed a star. But they disagree on exactly how it happened. Exciting possibilities include a black hole weighing a few thousand times the sun’s mass shredding a star that passed too close to it or a much smaller black hole merging with and consuming its stellar companion.

Eliza Neights at George Washington University in Washington and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said:

The initial wave of gamma rays lasted at least 7 hours, nearly twice the duration of the longest gamma-ray burst seen previously, and we detected other unusual properties. This is certainly an outburst unlike any other we’ve seen in the past 50 years.

Neights and other astronomers shared their results in October at the American Astronomical Society’s High Energy Astrophysics Division meeting in St. Louis, Missouri. Researchers have already published a variety of papers on the event, and more have been accepted or are being prepared.

An exceptional burst

Detected about once a day on average, gamma-ray bursts can appear anywhere in the sky with no warning. They are very distant events, with the closest-known example erupting more than 100 million light-years away.

The record-setting duration of the July burst – named GRB 250702B – places it in a class by itself. Of the roughly 15,000 gamma-ray bursts observed since astronomers first discovered the phenomenon in 1973, none are as long, and only a half dozen even come close. Because opportunities to study such events are so rare, and because they may reveal new ways to create gamma-ray bursts, astronomers are particularly excited about the July burst.

Most bursts last from a few milliseconds to a few minutes. Also, they’re known to form in two ways: either by a merger of two city-sized neutron stars or the collapse of a massive star once its core runs out of fuel. Each produces a new black hole. Some of the matter falling toward the black hole becomes channeled into tight jets of particles that stream out at almost the speed of light, creating gamma rays as they go. But neither of these types of bursts can readily create jets able to fire for days, which is why 250702B poses a unique puzzle.

Seeing the light

The Gamma-ray Burst Monitor on NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope discovered the burst. It triggered the instrument multiple times over the course of three hours. Also detecting the burst was: the Burst Alert Telescope on NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, the Russian Konus instrument on NASA’s Wind mission, the Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometer on Psyche – a NASA spacecraft currently en route to asteroid 16 Psyche – and Japan’s Monitor of All-sky X-ray Image instrument on the International Space Station.

Eric Burns is an astrophysicist at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge and a member of Neights’ team studying the burst’s gamma-ray glow. Burns said:

The burst went on for so long that no high-energy monitor in space was equipped to fully observe it. Only through the combined power of instruments on multiple spacecraft could we understand this event.

The Wide-field X-ray Telescope on China’s Einstein Probe also detected the burst in X-rays. And it showed that a signal was present the previous day. The first precise location came early July 3 when Swift’s X-Ray Telescope imaged the burst in the constellation Scutum, near the crowded, dusty plane of our Milky Way galaxy. Given this location and the day-earlier X-ray detection, astronomers wondered if this event might be a different type of outburst from somewhere within our own galaxy.

This visualization illustrates the process of pinpointing the location of the July 2 outburst and its host galaxy. Multiple facilities in space and on Earth, collecting light across the spectrum, guided astronomers to the source. Video via NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and A. Mellinger, CMU.

A galaxy behind our galaxy

Images from some of the largest telescopes on the planet, including those at the Keck and Gemini observatories on Hawaii and the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, hinted there was a galaxy at the spot. So astronomers turned to NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope for a clearer view.

Andrew Levan, an astrophysics professor at Radboud University in the Netherlands, led the VLT and Hubble study. Levan said:

It’s definitely a galaxy, proving it was a distant and powerful explosion, but it is a strange looking one. The Hubble data could either show two galaxies merging, or one galaxy with a dark band of dust splitting the core into two pieces.

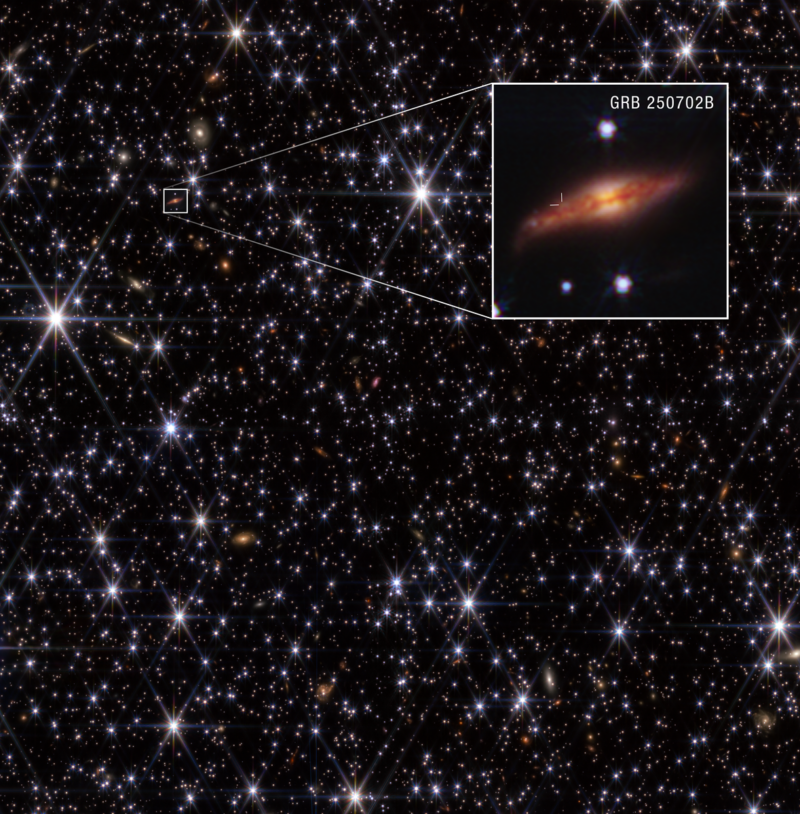

More recent images captured by the NIRcam instrument on NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope strongly support Levan’s interpretation. Huei Sears, a postdoctoral researcher at Rutgers University in New Jersey who led the NIRcam observations, said:

The resolution of Webb is unbelievable. We can see so clearly that the burst shined through this dust lane spilling across the galaxy. It’s fantastic to see the gamma-ray burst host in such detail.

This brief animation compares the brightness and duration of a typical gamma-ray burst (yellow) to that of the July 2 outburst (magenta). A typical burst lasts less than a minute. But GRB 250702B’s activity continued for more than 7 hours. Video via NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Gamma-ray burst of epic proportions

In late August, a team led by Benjamin Gompertz at the University of Birmingham in the U.K. used Webb’s NIRSpec instrument and the VLT to determine the galaxy’s distance and other properties. Gompertz said:

The burst was remarkably powerful, erupting with the equivalent energy emitted by a thousand suns shining for 10 billion years. Amazingly, the galaxy is so far away that light from this explosion began racing outward about 8 billion years ago, long before our sun and solar system had even begun to form.

A comprehensive study of the X-ray light following the main burst used observations from Swift, NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory and the agency’s NuSTAR (Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array) mission. Swift and NuSTAR data revealed rapid flares occurring up to two days after the burst’s discovery.

Study leader Brendan O’Connor, a McWilliams Postdoctoral Fellow at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, said:

The continued accretion of matter by the black hole powered an outflow that produced these flares, but the process continued far longer than is possible in standard gamma-ray burst models. The late X-ray flares show us that the blast’s power source refused to shut off, which means the black hole kept feeding for at least a few days after the initial eruption.

Conflicting evidence for the gamma-ray burst

Fermi and Swift data indicate a typical, if unusually long, gamma-ray burst. Spectroscopic Webb observations did not find a supernova explosion. These typically follow a stellar collapse gamma-ray burst. However, dust and distance might have obscured it. Einstein Probe saw X-rays a day before the burst, while NuSTAR tracked X-ray flares up to two days after. Neither is typical for gamma-ray bursts.

In addition, Jonathan Carney, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, led a detailed study that the host galaxy is different from the small galaxies that host most stellar collapse gamma-ray bursts. Carney said:

This galaxy turns out to be surprisingly large, with more than twice the mass of our own galaxy.

In either of the two most discussed scenarios, the black hole will have eaten the star in about a day.

The first invokes an intermediate-mass black hole, one with a few thousand solar masses and an event horizon – the point of no return – a few times larger than Earth. A star wanders too close and becomes stretched along its orbit by gravitational forces. Then the black hole rapidly consumes it. This describes what astronomers call a tidal disruption event, but one caused by a rarely observed “middleweight” black hole. Middleweight black holes have a mass much greater than those born in a stellar collapse and much smaller than the behemoths found in the centers of big galaxies.

A different scenario

But the gamma-ray team favors a different scenario. Because, if this burst is like others, the black hole’s mass must be more similar to our sun’s. Their model envisions a black hole about three times the sun’s mass – with an event horizon just 11 miles (18 kilometers) across – orbiting and merging with a companion star. The star is of similar mass to the black hole but much smaller than the sun. That’s because its hydrogen atmosphere has mostly been stripped away, down to its dense helium core, forming an object astronomers call a helium star.

In both cases, matter from the star first flows toward the black hole and collects into a vast disk, from which the gas makes its final plunge into the black hole. At some point in this process, the system begins to shine brightly in X-rays. Then, as the black hole rapidly consumes the star’s matter, gamma-ray jets blast outward.

Notably, the helium star merger model makes a unique prediction. Once the black hole is totally immersed within the main body of the star, feasting on it from within, the energy it releases explodes the star and powers a supernova.

Unfortunately, this explosion occurred behind enormous amounts of dust, meaning even the power of the Webb telescope was not enough to see the expected supernova. While smoking-gun evidence to explain what happened on July 2 will have to wait for future events, 250702B has already provided new insight into the longest gamma-ray bursts. That’s thanks in large part to the constant cosmic monitoring of NASA’s fleet of observatories and instruments as part of the agency’s quest to explore and understand the universe.

A peek at the host galaxy

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society has accepted the Neights-led gamma-ray paper for publication. The Astrophysical Journal Letters – which published the Carney paper November 26, the O’Connor X-ray paper on November 14, and the Levan paper on August 29 – has accepted the Gompertz NIRSpec paper for publication.

Bottom line: We now have more insight on the longest gamma-ray burst yet. The burst lasted at least seven hours, nearly double that of the previous record.

Via NASA