- Astronomers look for signatures of alien life in starlight. When a distant planet passes in front of its star, the signature of molecules in the exoplanet’s atmosphere show up in the star’s rainbow array of colors.

- Certain molecules could indicate the presence of life, even from many light-years away. The detection of dimethyl sulfide, for example, could point to alien life.

- New telescopes coming online could aid this research. Some of the telescopes that will help astronomers see alien atmospheres include the Nancy Grace Roman Telescope and the Habitable Worlds Observatory.

EarthSky’s 2026 lunar calendar shows the moon phase for every day of the year. Available now. Get yours today!

By Carole Haswell, The Open University

How to detect signatures of alien life in exoplanet air

We live in a very exciting time: answers to some of the oldest questions humanity has conceived are within our grasp. One of these is whether Earth is the only place that harbors life.

In the last 30 years, the question of whether the sun is unique in hosting a planetary system has been resoundingly answered: we now know of thousands of exoplanets orbiting other stars.

But can we use telescopes to detect whether any of these distant worlds also harbor life? A promising method is to analyze the gases present in the atmospheres of these planets.

We now know of more than 6,000 exoplanets. With so many now cataloged, there are a number of ways to narrow down which worlds are the most promising for biology. Using the planet’s distance from its host star, for example, astronomers can work out its likely temperature.

Earth is the only planet in the solar system with liquid water oceans on its surface, so mild temperatures are a possible requirement for a habitable planet. Whether a planet has the correct temperature for liquid water is strongly influenced by the presence and nature of the planet’s atmosphere.

Atmospheres on exoplanets

Astonishingly, we can identify molecules present in the atmospheres of exoplanets. Quantum mechanics causes each atmospheric chemical to have its own distinct barcode-like pattern, which it leaves on the light passing through it. By collecting starlight that has been filtered through an exoplanet’s atmosphere, telescopes can see the barcodes of the molecules making up that atmosphere.

To take advantage of this, the planet needs to transit – pass in front of – the star from our point of view. This means it only works for a small fraction of known exoplanets.

The strength of the signal depends on the abundance of the molecule in the atmosphere: stronger for the most abundant molecules and gradually weaker as the abundance decreases. This means it is generally easiest to detect the dominant molecules, though this is not always true. Some of the barcodes are intrinsically strong, while others are weak.

For example, Earth’s atmosphere is dominated by diatomic nitrogen (N2). But this molecule has a feeble barcode compared to the much less abundant diatomic oxygen (O2), ozone (O3), carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O).

Detecting molecules

The James Webb Space Telescope is a large space telescope that collects light at infrared wavelengths. Astronomers have used it to probe the atmospheres of a variety of exoplanets.

The detection of molecular imprints in the atmosphere of an exoplanet is not completely straightforward. Different teams of workers can derive different results as a consequence of making slightly different choices in the way they handle the same data. But despite these difficulties, researchers have made reproducible and robust detections of molecules. Astronomers have detected simple molecules with strong barcodes such as methane, carbon dioxide and water.

Planets larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune – so called sub-Neptunes – are the most common type of known exoplanet. It was for one of these planets, K2-18b, that researchers made a bold claim of a detection of a biosignature in 2025. The analysis detected dimethyl sulfide, with a claimed less-than-one-chance-in-1,000 that this detection was spurious.

On Earth, phytoplankton in the oceans produces dimethyl sulfide. But it rapidly breaks down in seawater illuminated by sunlight. As K2-18b may be a planet completely covered by a water ocean, the detection of dimethyl sulfide in its atmosphere could imply an ongoing supply of it from microbial marine life there.

Questions remain

Re-examination of the K2-18b dimethyl sulfide detection by other researchers casts doubt on this claim. Most significant was the 2025 demonstration by Arizona State University’s Luis Welbanks and colleagues that the choice of molecular barcodes to include in the analysis radically affected the results.

They found that numerous alternatives, not explored in the original paper, provided equally good or better fits to the measured data.

For Earth-sized planets that are presumably rocky, it is quite challenging to detect an atmosphere at all with Webb. However, the future is promising, as a number of planned missions will allow us to learn a lot more about planets which may be similar to Earth.

Upcoming missions

With a planned launch in January 2027, the European Space Agency’s Plato telescope will identify planets far more similar to Earth and suitable for transmission spectroscopy than those we currently know of.

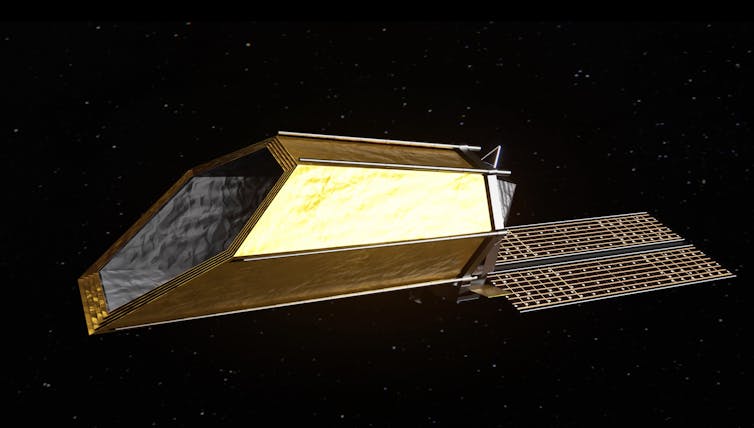

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which is set to launch in May 2027, will pioneer coronagraphic techniques. These techniques will allow starlight to be canceled out so astronomers can study the much dimmer planets orbiting nearby stars directly.

The European Space Agency’s Ariel telescope, with a planned launch in 2029, is a dedicated transmission spectroscopy mission. It’s designed to have the capabilities to determine the compositions of exoplanet atmospheres.

NASA’s Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) is currently in the planning stages. This mission will use a coronagraph to study around 25 Earth-like planets, looking for a variety of hallmarks of habitability.

HWO will have broad wavelength coverage from the ultraviolet out to the near-infrared. If a twin of Earth were orbiting one of HWO’s nearby target stars, the telescope would collect the starlight reflected from the planet. This reflected starlight would include the barcode signatures of diatomic oxygen and other gases characteristic of our planet’s atmosphere. It would also reveal a signature of starlight being absorbed by photosynthesizing plants: the so-called “vegetation red edge”.

Earth’s surface – split between land and oceans – reflects light differently. HWO would be able to reconstruct a low-resolution map of the surface from the changes in the reflected light as continents and oceans rotate in and out of view.

The future of detecting signatures of alien life

So the future looks very promising. With the spacecraft set to launch in coming years, we might close in on the question of whether Earth is unique in hosting life.![]()

Carole Haswell, Professor of Astrophysics, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: Astronomers can detect the molecules of distant exoplanets when they pass in front of their stars. These molecules might help reveal signatures of alien life.

Read more: The tally is in! 6,000 exoplanets now confirmed

Read more: Colorful life on exoplanets might be lurking in clouds