On Dec. 17, 1903, humanity’s long-held dream of flying came true. Ideas of flying date back centuries, from the Greek legend of Icarus and Daedalus, to kite flying in China, to the development of hydrogen-filled balloons in 18th century France, to early experiments with gliders in 19th century England and Germany. Around the turn of the 20th century, advances in engine technology and aerodynamics enabled powered flight using heavier-than-air machines, but attempts by leading designers proved unsuccessful. The honor of the first sustained and controlled flight of a powered heavier-than-air aircraft went to two bicycle shop owners from Dayton, Ohio, Orville and Wilbur Wright. The brothers combined the mechanical experience from their business with the fundamental breakthrough invention of three-axis control to enable them to steer the aircraft and maintain its equilibrium. Their 12-second flight changed the world forever.

Left: Orville Wright during the first powered flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft; Wilbur is standing to the right of the aircraft. Right: The Wrights’ third flight on Dec. 17, 1903. Image credits: courtesy National Park Service.

After several unsuccessful attempts, on Dec. 17, 1903, at Kill Devil Hills near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Orville Wright completed the first powered flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft known as the Wright Flyer. The flight lasted just 12 seconds, traveled 120 feet, and reached a top speed of 6.8 miles per hour. Amazing for the day, one of the five people to witness this historic first flight snapped a photograph of the event. The brothers completed three more flights that day, taking turns piloting, the longest traveling 852 feet in 59 seconds. The highest altitude reached in any of the flights was about 10 feet. The aircraft sustained damage at the end of its fourth flight, and gusty winds tipped it over, wrecking it beyond repair. The aircraft never flew again, but Orville took the wreckage home to Ohio and restored it. It went on display at the London Science Museum until 1948 when the Smithsonian Institution took ownership. Visitors can view the Wright Flyer in the Wright Brothers & The Invention of the Aerial Age exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, D.C.

Distant view of the Wright Flyer, at left, after its fourth flight on Dec. 17, 1903. Image credit: courtesy Library of Congress.

Bronze statues recreate the day of the first powered flight at the Wright Brothers National Memorial near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Image credit: courtesy National Park Service.

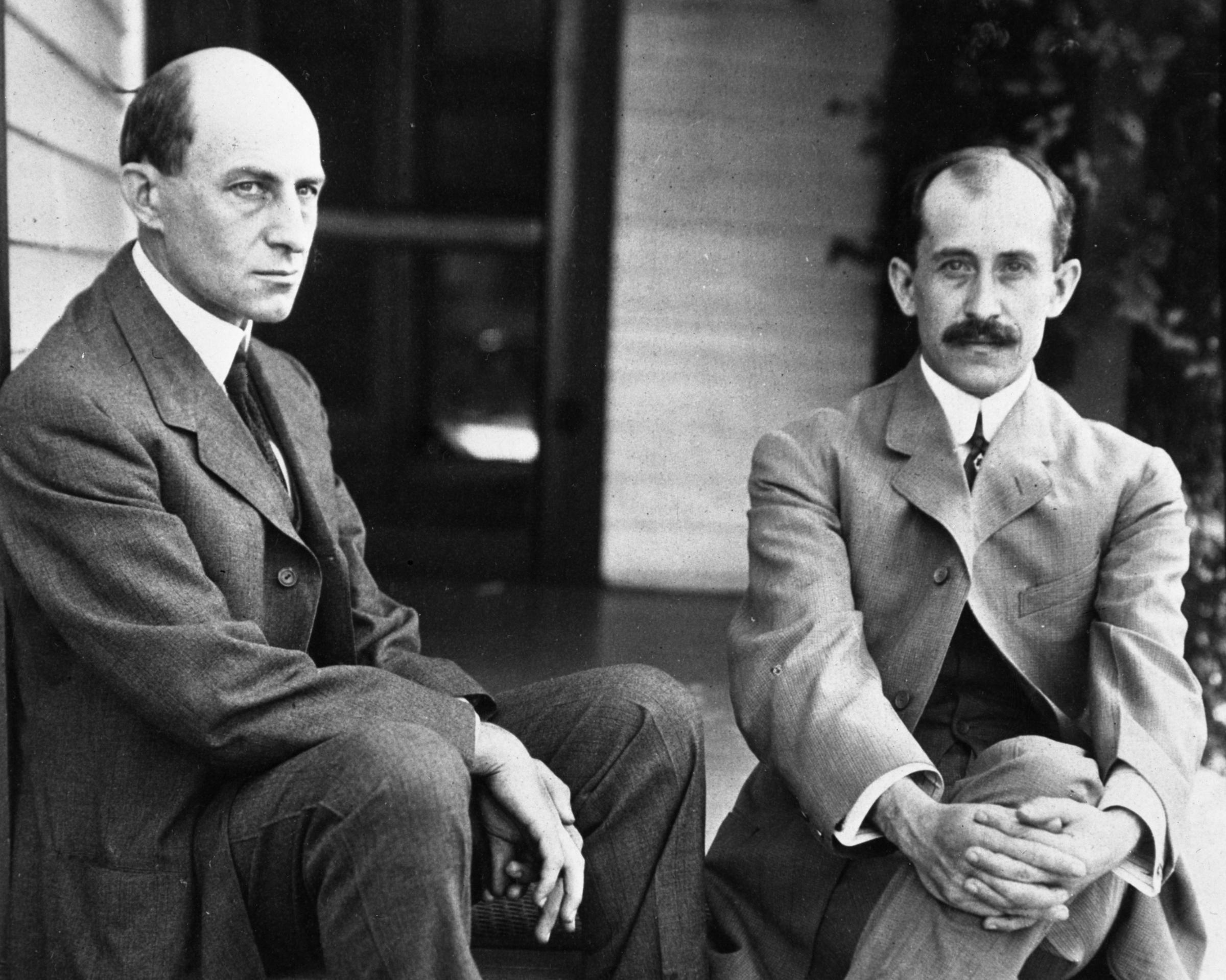

Left: Wilbur, left, and Orville Wright. Image credit: courtesy Carillon Historical Park. Right: The Wright Flyer at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, D.C. Image credit: courtesy NASM.

The Wrights continued flying, building more and more advanced aircraft, and paving the way for future aerial explorers. By 1905, they completed a 24-mile flight in their Flyer III. Others in the United States and Europe made advances in the rapidly expanding field of aviation, and World War I (1914-1918) saw the first use of aircraft in warfare. The first scheduled commercial passenger flight took place on Jan. 1, 1914, between St. Petersburg and Tampa, Florida, shortening travel between the two cities by more than 90 minutes. The Post Office emerged as one of the first major users of airplanes to speed up the delivery of mail across the country.

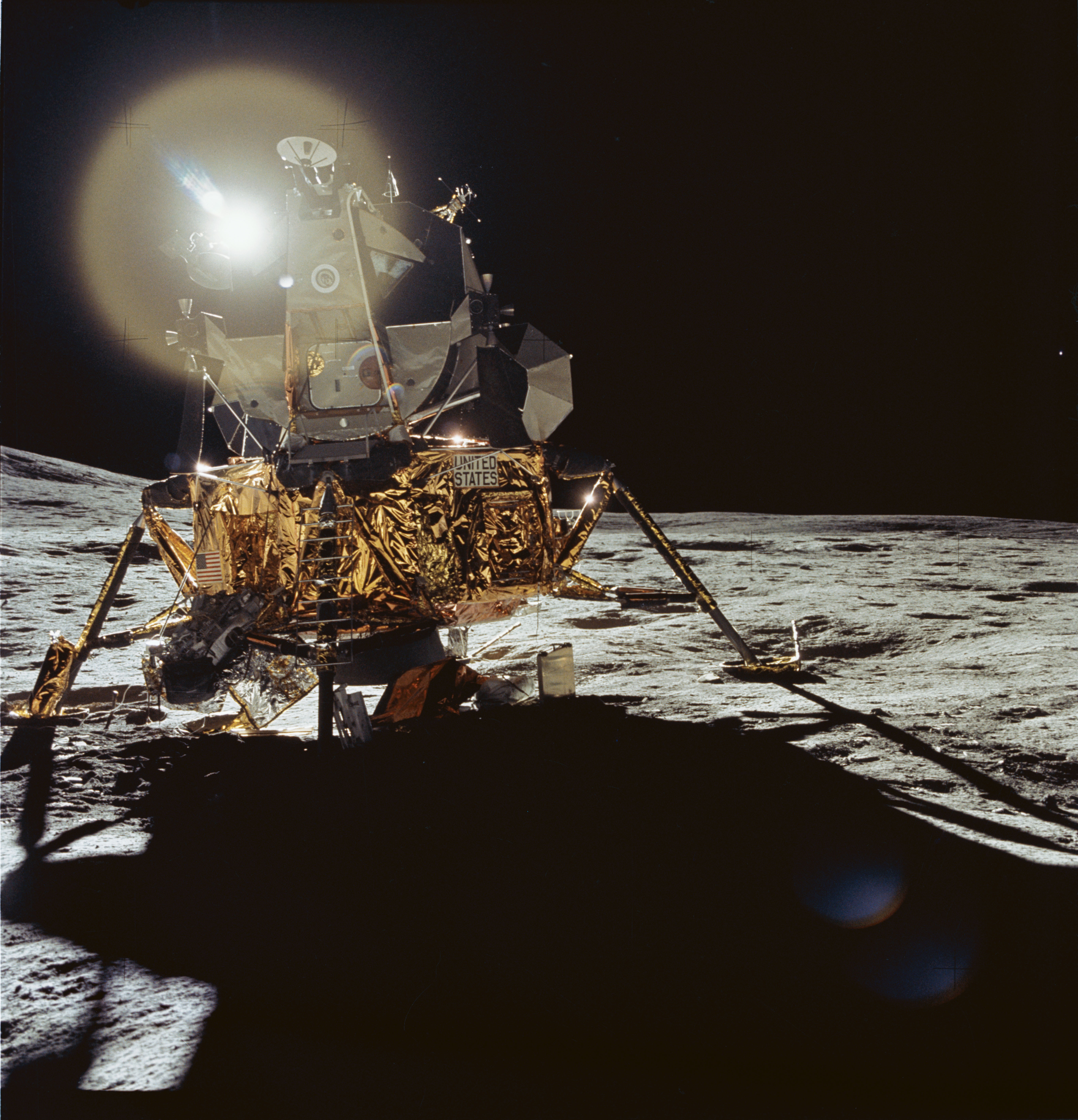

Left: Seal of NACA, including an illustration of the first flight at Kitty Hawk. Middle: Seal of NASA. Right: Apollo 14 Lunar Module Kitty Hawk on the surface of the Moon.

Within a dozen years after the first powered flight, the U.S. government formed the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA) to advance the field of aeronautics. Research conducted at NACA facilities – Langley Aeronautical Laboratory in Hampton, Virginia; Ames Aeronautical Laboratory in Mountain View, California; Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio; and Muroc Flight Test Unit at Edwards Air Force Base near Lancaster, California – led to breakthroughs that greatly advanced the field of aeronautics including supersonic flight. In 1958, in response to Soviet advances in space flight, the U.S. government established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), a civilian agency to lead American space activities. At its core, the new agency incorporated NACA’s facilities and employees. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy gave NASA the goal of landing a man on the Moon within the decade. Just 65 years after the Wrights made their pioneering flight on the sands of Kitty Hawk, Apollo 11 astronauts left humanity’s first footprints on the dusty surface of the Moon. To honor the Wrights’ accomplishment, the Apollo 14 astronauts named their Lunar Module Kitty Hawk.

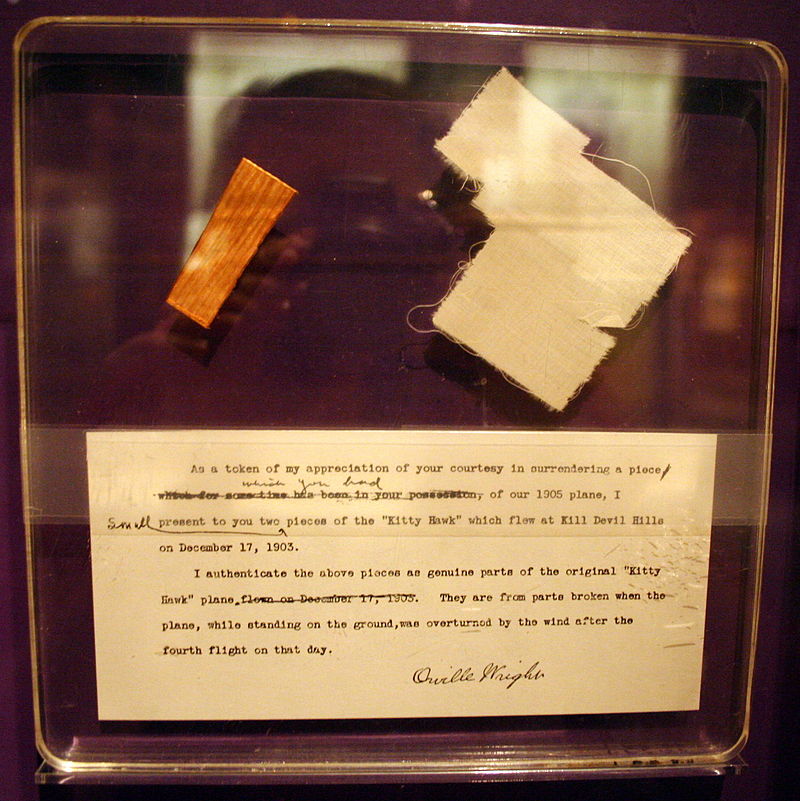

Left: Display of the wood and fabric pieces of the Wright Flyer that Apollo 11 astronaut Neil A. Armstrong took to the Moon. Image credit: courtesy National Air and Space Museum. Right: Display of the pieces of wood and fabric from the Wright Flyer that launched on space shuttle Challenger’s STS-51L mission and recovered from the wreckage. Image credit: courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Pieces of the Wright Flyer, sometimes called Kitty Hawk, have flown in space, carried there by astronauts with a geographic connection and a sense of history. In 1969, under a special arrangement with the U.S. Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio, Apollo 11 astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, like the Wright brothers a native of Ohio, took with him a piece of wood from the Wright Flyer’s left propeller and a piece of muslin fabric (8 by 13 inches) from its upper left wing. The items, stowed in his Lunar Module Eagle personal preference kit, landed with him and fellow astronaut Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin at Tranquility Base, and returned to Earth with third crew member Michael Collins in the Command Module Columbia. Visitors can view these items near the Wright Flyer at the NASM. In 1986, North Carolina native NASA astronaut Michael J. Smith arranged with the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh to take a piece of wood and a swatch of fabric salvaged, and authenticated by Orville Wright, from the damaged Wright Flyer aboard space shuttle Challenger’s STS-51L mission. Although Challenger and its crew perished in the tragic accident, divers recovered the artifacts from the wreckage and visitors can view them at the North Carolina Museum of History. Astronaut John H. Glenn, an Ohioan like the Wrights and Armstrong, took different pieces of the Wright Flyer when he returned to space aboard STS-95 in 1998. In October 2000, North Carolina native NASA astronaut William S. McArthur, on behalf of North Carolina’s First Flight Centennial Commission, flew a piece from the Wright Flyer donated by the National Park Service. McArthur carried a fragment of muslin fabric from the aircraft’s wing to the International Space Station during the STS-92 mission, the 100th space shuttle flight, to promote the then-upcoming 100th anniversary of the first powered flight.

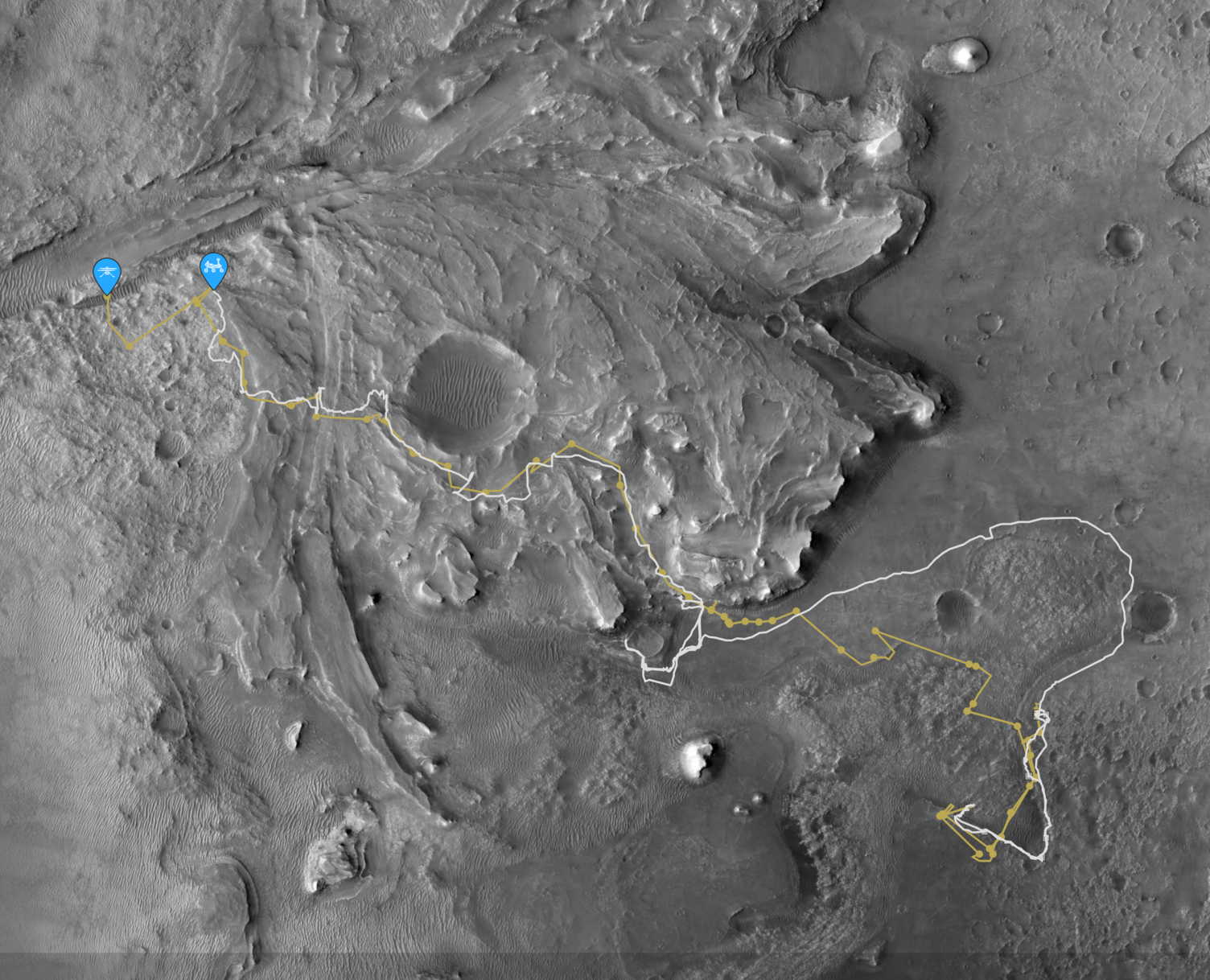

Left: The autonomous helicopter Ingenuity, near center of photograph, makes the first powered flight on Mars, imaged by the Perseverance rover. Middle: Routes of the Perseverance rover, white, and the Ingenuity helicopter, yellow, in Mars’ Jezero Crater. Right: A piece of cloth from the Wright Flyer’s wing attached to the underside of Ingenuity’s solar panel.

A piece of the Wright Flyer has even traveled beyond the Earth-Moon system. When the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover landed in Mars’ Jezero Crater on Feb. 18, 2021, it carried underneath it a four-pound autonomous helicopter named Ingenuity. Engineers attached a small piece of cloth the size of a postage stamp from the Wright Flyer’s wing to a cable underneath the helicopter’s solar panel. On April 19, 2021, when Ingenuity lifted off to a height of 10 feet, it marked the first powered aircraft flight on a world other than Earth. Ingenuity’s first flight lasted 39 seconds in an area NASA named Wright Brothers Field. The United Nations International Civil Aviation Organization gave the field the airport code of JZRO – for Jezero Crater – and the helicopter type designator IGY, with the call-sign INGENUITY. With no humans present to record the event, the Perseverance rover imaged Ingenuity’s first flight. As of Dec. 2, 2023, Ingenuity has completed 67 flights over 947 Sols, far exceeding its technology demonstration goal of five flights over 30 Sols (Martian days), with a total flight time of 2 hours 1 minute 5 seconds, traveling a total distance of 9.6 miles and reaching a maximum altitude of 78.7 feet. Its ground-breaking mission continues, paving the way for future aerial explorers of Mars.