- Water vapor plumes may spew from the surfaces of several icy moons in the outer solar system, including Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa. The plumes originate in subsurface oceans on these worlds.

- Spacecraft, such as Europa Clipper, might be able to detect traces of microscopic life, including lipids or fatty acids, in tiny ice grains within the water vapor plumes.

- Any possible microorganisms in the plumes might be similar to cold water bacteria on Earth, such as Sphingopyxis alaskensis.

Microscopic life on ocean moons?

Is there life on any ocean moon in our solar system? These worlds have subsurface oceans beneath icy crusts. Instead of plunging into the ocean, we can analyze their water vapor plumes. We know such plumes occur on Saturn’s moon Enceladus. And there’s growing evidence for water vapor plumes on Europa as well. On March 22, 2024, researchers in the U.S, the U.K. and Germany published a new study showing how traces of microscopic life could be detected in tiny ice grains carried upward from these worlds’ oceans, through their ice crusts, via the plumes. The researchers said that instruments on Europa Clipper and other future missions might even be able to find tiny amounts of cellular material.

Join us in making sure everyone has access to the wonders of astronomy. PLEASE DONATE!

Scientists from the University of Washington in Seattle; the University of Colorado, Boulder; NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory; The Open University in the U.K and the Freie Universität Berlin and University of Leipzig in Germany all contributed to the new study. The journal Science Advances published their peer-reviewed findings on March 22, 2024.

Cellular material detectable in ice grains of ocean moons

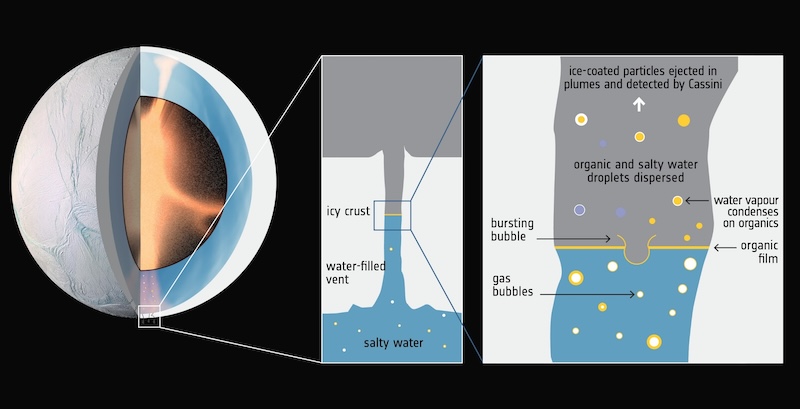

The water vapor plumes of Saturn’s moon Enceladus – and perhaps Europa, if Jupiter’s moon has plumes, too – contain water, ice grains, organic compounds and other molecules. On Enceladus, scientists know these materials originate from the global ocean below the moon’s outer ice shell. If there is, or was, any microscopic life in that ocean, could there be traces of it in the ice grains? And could a spacecraft detect them?

Lead author Fabian Klenner, a postdoctoral researcher in Earth and space sciences at the University of Washington said yes:

For the first time we have shown that even a tiny fraction of cellular material could be identified by a mass spectrometer onboard a spacecraft. Our results give us more confidence that using upcoming instruments, we will be able to detect lifeforms similar to those on Earth, which we increasingly believe could be present on ocean-bearing moons.

Preparing for future missions to ocean moons

In order to prepare for missions that could find evidence of life, including NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper, the researchers are testing how the instruments might detect it. With this in mind, they sent a thin beam of water into an airless vacuum. Consequently, with no air pressure, the beam disintegrated into separate droplets. To mimic the spacecraft’s instruments, the team used a laser beam to excite the droplets. Mass spectral analysis instruments then examined the droplets.

The results showed that, yes, the instruments can detect tiny bits of cellular material with great precision; in fact, in one out of hundreds of thousands of ice grains.

The researchers used a common bacterium called Sphingopyxis alaskensis. It exists in ocean waters off Alaska. It is single-celled and adapted to the cold environment. Scientists think it’s a good example of the kind of microscopic life that might be found on ocean moons. They’re also so small that one bacterium could fit inside one ice grain. Klenner said:

They are extremely small, so they are in theory capable of fitting into ice grains that are emitted from an ocean world like Enceladus or Europa.

If something like Sphingopyxis alaskensis exists on ocean moons, the instruments would be able to find it, or at least remnants of it.

The experiments also showed that it might be more successful to analyze small samples in individual ice grains, rather than larger samples consisting of billions of ice grains.

Riding in gas bubbles

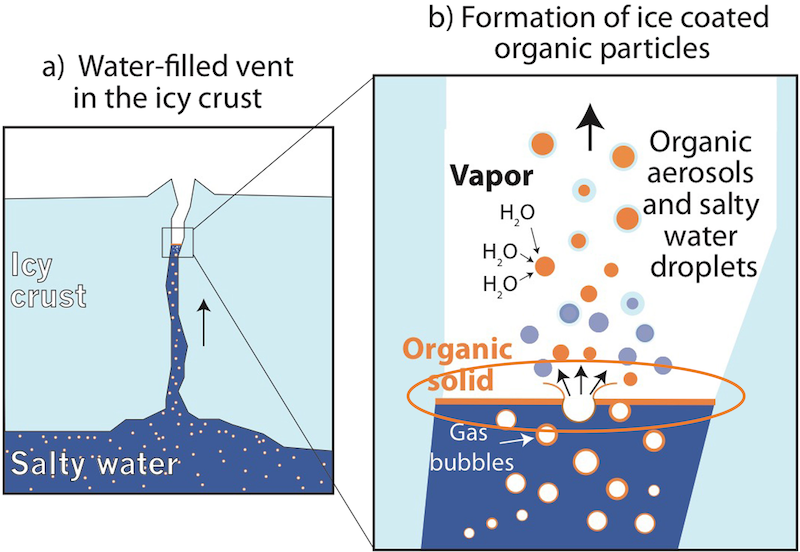

If there are microbes in the ocean, how would they get into the plumes? If they’re similar to earthly bacteria like Sphingopyxis alaskensis, then it might be quite easy. The researchers said the bacterial cells might be inside lipid membranes. On Earth, they form a skin on the ocean’s surface, commonly called ocean scum.

On an ocean moon, the water reaches the surface through cracks in the ice shell. Scientists call the ones on Enceladus tiger stripes. The ocean water, containing gas bubbles, reaches the surface through the cracks. It then rapidly boils since there’s no atmosphere on the moon to speak of, just the vacuum of space. The gas bubbles burst, releasing any material they contain, including organics. That material then becomes trapped inside the ice grains that form within the plume spray. Klenner said:

We here describe a plausible scenario for how bacterial cells can, in theory, be incorporated into icy material that is formed from liquid water on Enceladus or Europa and then gets emitted into space.

A visiting spacecraft like Europa Clipper could then sample the ice grains in the plumes, or even ones that have fallen back onto the moon’s surface.

Looking for lipids and fatty acids

The Cassini spacecraft analyzed the plume spray on Enceladus. But its instruments were a bit limited in detecting organic molecules directly associated with life. That includes like lipids or fatty acids. As Klenner noted:

For me, it is even more exciting to look for lipids, or for fatty acids, than to look for building blocks of DNA, and the reason is because fatty acids appear to be more stable.

Frank Postberg, a professor of planetary sciences at the Freie Universität Berlin in Germany, added:

With suitable instrumentation, such as the Surface Dust Analyzer on NASA’s Europa Clipper space probe, it might be easier than we thought to find life, or traces of it, on icy moons … If life is present there, of course, and cares to be enclosed in ice grains originating from an environment such as a subsurface water reservoir.

Bottom line: A new study from an international team of scientists shows that it might be possible to detect microscopic life in ice grains in the plumes of ocean moons like Enceladus or Europa.

Source: How to identify cell material in a single ice grain emitted from Enceladus or Europa

Via University of Washington

Read more: How ice shells of ocean moons provide clues to habitability

Read more: Death Star moon Mimas has a hidden ocean